Frontend Web Debugging Techniques : Isolation

So, I’ve been talking with a few friends lately about this idea of “good habits” with regards to front end web development and I started stewing on a bunch of ideas on how I could write about something like that in an effective way. Sorry to say that this blog post will not be about good habits relating to code but rather as they relate to debugging front end code. I think the latter is valuable and you’ll still get a decent idea of some good habits to work with going forward. Enough rambling, onward!

Isolation, Your First Stop

You’ve just fired up your browser and checked out an existing application from your repository of choice. You get the app running and go to take a look at the state of the front end because you have a bug to fix. A nice shiny red bug sitting there in front of you. Eager to dig in you open Firebug / Webkit Inspector and find yourself looking at no less than 50 separate CSS files and 40 javascript files. YIKES!

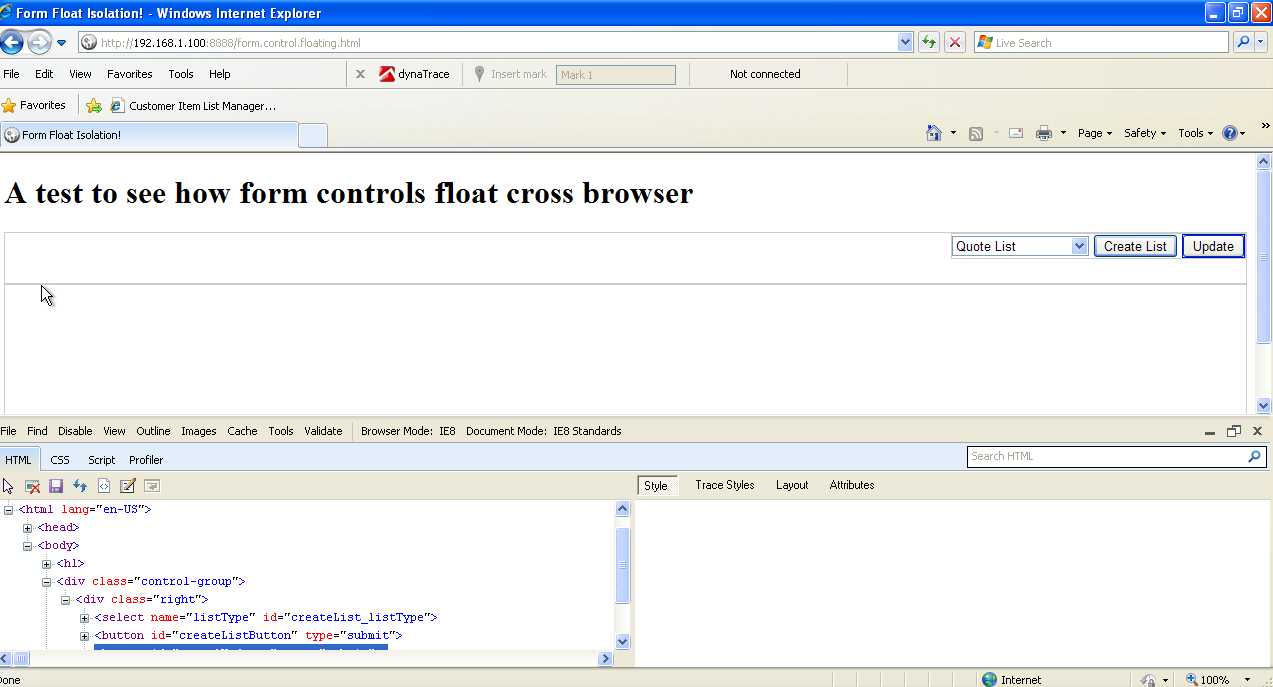

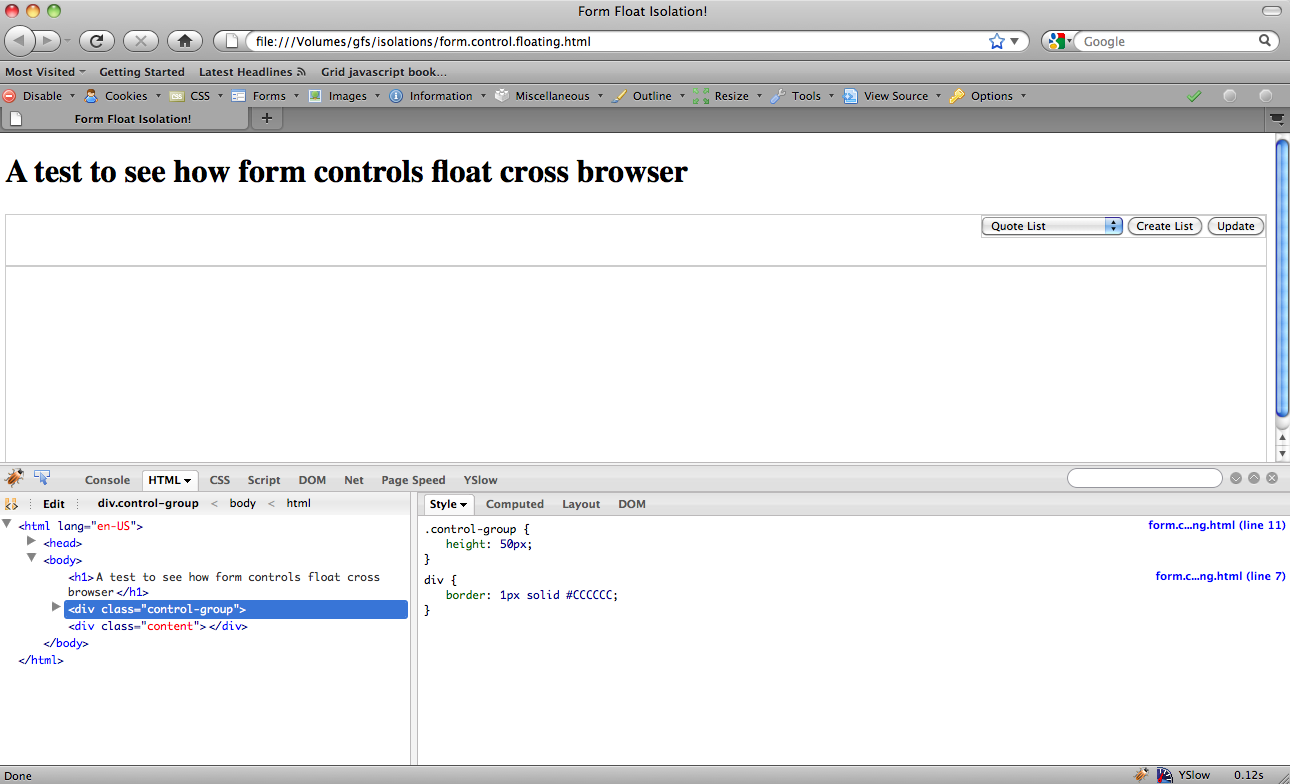

The bug card you have says some buttons aren’t appearing properly in IE7 and the latest Chrome. So you dive in with your front end tweaker and start disabling styles dynamically hoping you can affect some change in the cascade that will fix the bug live in the browser right there in front of you. Bam! Looks good in Firefox/Chrome and then you open IE and things go to hell. Sound familiar?

It’s at this point that you should really stop what you’re doing and try to isolate the problem. I’ve spent more than enough time hacking in this way to know that it’s a lost cause and infinitely frustrating to boot. The best way to fix a rendering issue in a case like this is to isolate your problem so you can control the number of variables you are testing.

Here’s how I like to break down my isolation debugging process:

1. Create a Test Case

Open a new html file in Textmate or your favorite code editor and create a brand new HTML page. I like to keep a skeleton page so I can do this quickly. This page should have no stylesheets or scripts loaded.

2. Replicate the Environment

Bring the HTML in question into your sample page as it appears in your production code. Also bring only the CSS that applies to those elements and put them in a style block in the head of your sample page.

3. Verify

You probably have some assumptions about what you think the problem is, this is the step where you verify that. Open your sample page in the browsers you want to test in and see what kind of results you get. The goal here is to eliminate the thousands of lines of other CSS and JavaScript that might be altering the way your markup is displayed.

4. Refactor

Once you’ve verified things are behaving the way you want you should probably refactor that HTML and CSS to contain less presentation in your markup. Often markup from legacy applications has been touched by many different people with varying interpretations about how to write HTML; that’s ok but given you spent the time to isolate this problem you may as well do some cleanup.

5. Verify … Again

You’ve made changes, run your test page through the browsers you are testing for again. Repeat step 4 and 5 until you’ve got a good baseline to work with. It’s also good to remember the answer to the question “Do websites need to look exactly the same in every browser?” NO.

6. Integrate

You were able to eliminate a bunch of redundant CSS selectors and redundant markup. Great! Now it’s time to inject your newly refactored code back into the mess of 50 CSS and 40 javascript files. This can be challenging based on how many dependencies you touched in your refactoring but at least you have a baseline of what to expect now.

Integration is going to result in some more rendering anomalies but now you have a core set of solid CSS/HTML that you know will work. What you do now is go through Firebug/Webkit Inspector and start disabling styles in the cascade that also affect your elements until you get the result you are looking for.

Conclusions

You will probably still have to fiddle but at least you will have eliminated a significant amount of frustration by isolating the problem and proving out your assumptions about how the markup and css will behave in other browsers. Of course you could avoid a significant amount of this cross browser troubleshooting by using something like Compass and SASS, but that’s a topic for another blog post ;)

I hope this was helpful to you and I wish you luck on improving your frontend debugging process and reducing the amount of frustration experienced.