Deterministic Core, Agentic Shell

The release of Gary Bernhardt’s screencast Functional Core, Imperative Shell mentioned at the end of his talk Boundaries was a transformational moment for me. Up until that point in my career, I hadn’t really thought too much about “architecture” as it relates to software, well at least not in the way I had heard software architects speak about it, which was, to my eager-but-naive ears, filled with a bunch of buzzwords and acronyms that I did not understand.

I have returned to both the screencast and talk many times because the concepts are packed with wisdom that continues to shape my thinking; it is evergreen content, you should watch both.

Gary’s insight was that separating the pure from the effectful lets you test what matters and push complexity to the edges. I think we’re at a similar inflection point now — but the “shell” has become something far more unpredictable than imperative I/O. The shell is now an LLM.

Where I Learned State Machines

From ~2008-2011 I worked at my first startup, Vendasta Technologies. They’re still around, and doing well, and dare I say had some of the best startup marketing of the 2000’s. Seriously just watch this 40 second spot riffing on how we named the company and tell me you didn’t laugh out loud …

The beauty of startups is twofold in my mind: you get to work with great people and you are forced to wear many hats. A few of those great people are folks who I deeply respect and admire, who have all gone onto greater things:

- Kevin Pierce was the person who got me into software development as a career in the first place and graciously spent time mentoring me at coffee-shops in Saskatoon, SK, answering all of my questions and helping me connect the dots when all I really knew was web frontend tech.

- Shawn Rusaw introduced me to the idea of expressing workflows and logic via finite state machines (FSMs) and did deep research into whitepapers on FSM architecture that shaped how our team built systems.

- Jason Collins was the CTO who led all of our teams and made all of the experimental ideas come to life knowing exactly how to put all the pieces together.

One of the highlights of working at Vendasta was the chance to get exposure to a ton of ideas; state machines resonated with me in particular because of how elegantly they enabled complex workflows to be built on top of simple concepts.

An early project the team built called MashedIn — which mashed your accounts from Twitter, LinkedIn, and Facebook to surface common connections — was where I began to connect the dots on these concepts.

MashedIn needed async workflows — fan-out across multiple social media APIs, reconciliation, deduplication — and the team built an async state-machine workflow engine in Python called Fantasm to power them. I recall eagerly watching demos and listening to Shawn speak about how it all fit together.

It was the first thing we open-sourced as a company, and Shawn, Kevin, and Jason were instrumental in making it happen on the beta version of AppEngine (what would eventually become a part of GCP).

It got so popular at the time that it was featured on the AppEngine blog. You can see how it has evolved on GitHub.

I want to underscore this was back in 2011!

Foundations of State Machines

Finite state machines trace back to the 1950s and 60s — Mealy (1955) and Moore (1956) formalized the two canonical FSM models, and they became foundational in compiler design, protocol specification, and hardware engineering. Shawn and the team at Vendasta took those ideas and made them practical for web-scale async workflows.

Fantasm’s FSM implementation was inspired by a later paper, published in 1999 by Jilles van Gurp and Jan Bosch: On the Implementation of Finite State Machines, and a talk by Brett Slatkin at Google I/O 2010 titled Building high-throughput data pipelines with Google AppEngine.

I re-read the paper this morning, and what struck me was how much it anticipates what came later. Their assessment section walks through how easy it is to add a new state — you just add a line of XML and retarget some transitions.

Their future work section even calls out conditional transitions (“transitions that only occur if the trigger event occurs and the condition holds true”) and Statechart support (“normal FSMs + nesting + orthogonality + broadcasting events”) — which is literally what XState implements today with guards, nested states, parallel states, and the sendTo/raise event system.

They also call out the need for “tracing and debugging tools” to keep track of what’s happening in the context — which is pretty much where XState’s Stately Inspector and Stately Studio have landed, giving you live statechart visualizations and sequence diagrams, but I digress.

The point I really wanted to make was, since my time at Vendasta, I have repeatedly returned to the concepts of finite state machines, and often found myself migrating business logic that was in the form of a poorly-specified-hidden-half-baked state machine into an actual state machine with transitions, guards, and easily unit-tested logic.

If there’s a golden hammer I think is actually worth swinging at every codebase, it’s definitely state machines.

(And if this wasn’t enough to summon David K. Piano, I don’t know what is). 😛

The Pattern Repeats

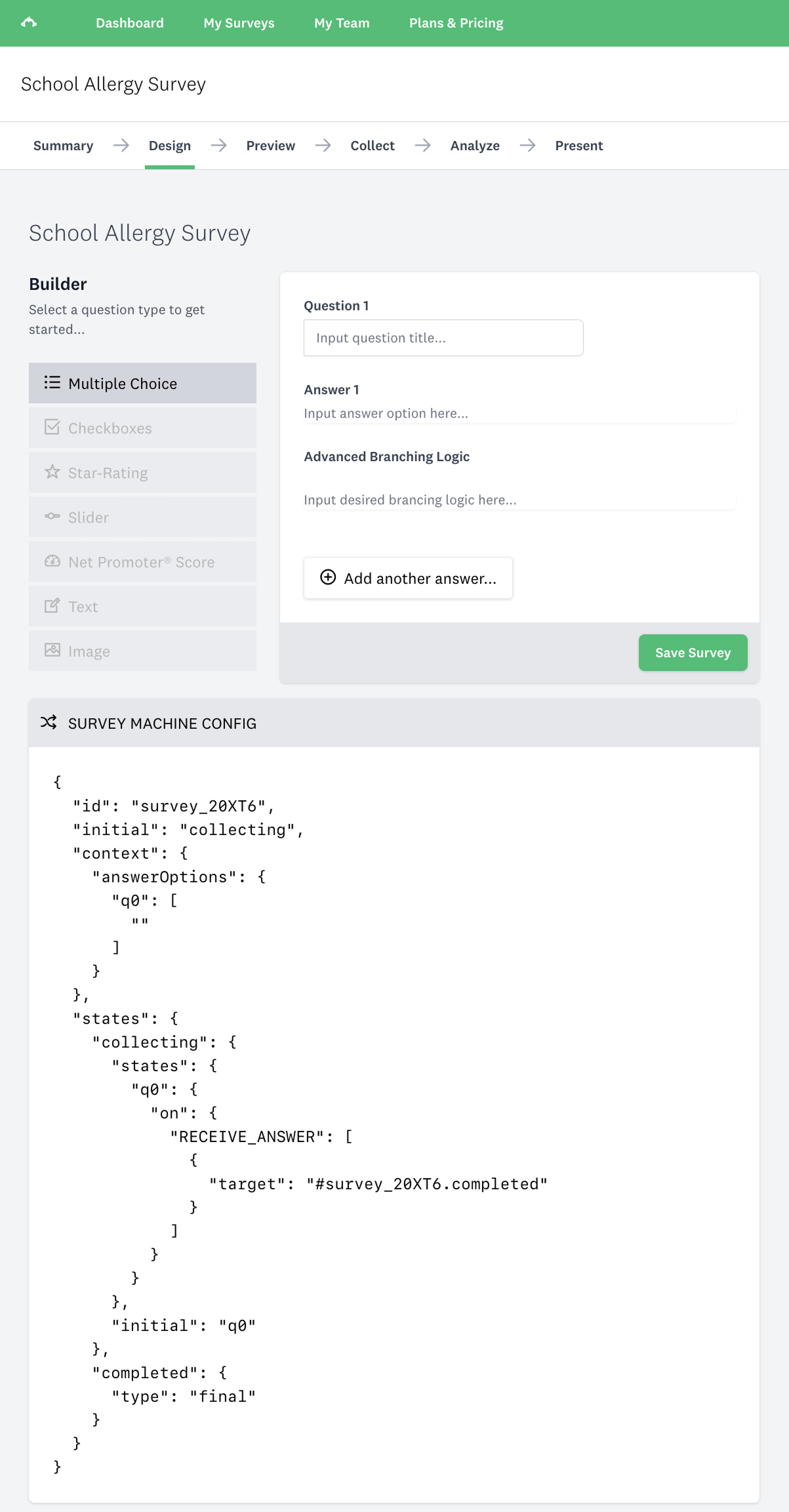

Five years ago I was working at SurveyMonkey as part of the Analyze team. The survey product was composed of a few pieces that fit together in a workflow:

Design -> Preview -> Collect -> Analyze -> Present

At the time, my team was tasked with coming up with a vision for how we could improve the Analyze experience for users; it had been built with a custom JavaScript framework that was difficult to follow, frequently violated Locality of Behaviour due to sprawl, had very fuzzy architectural boundaries, and made heavy use of event-driven architecture that was opaque.

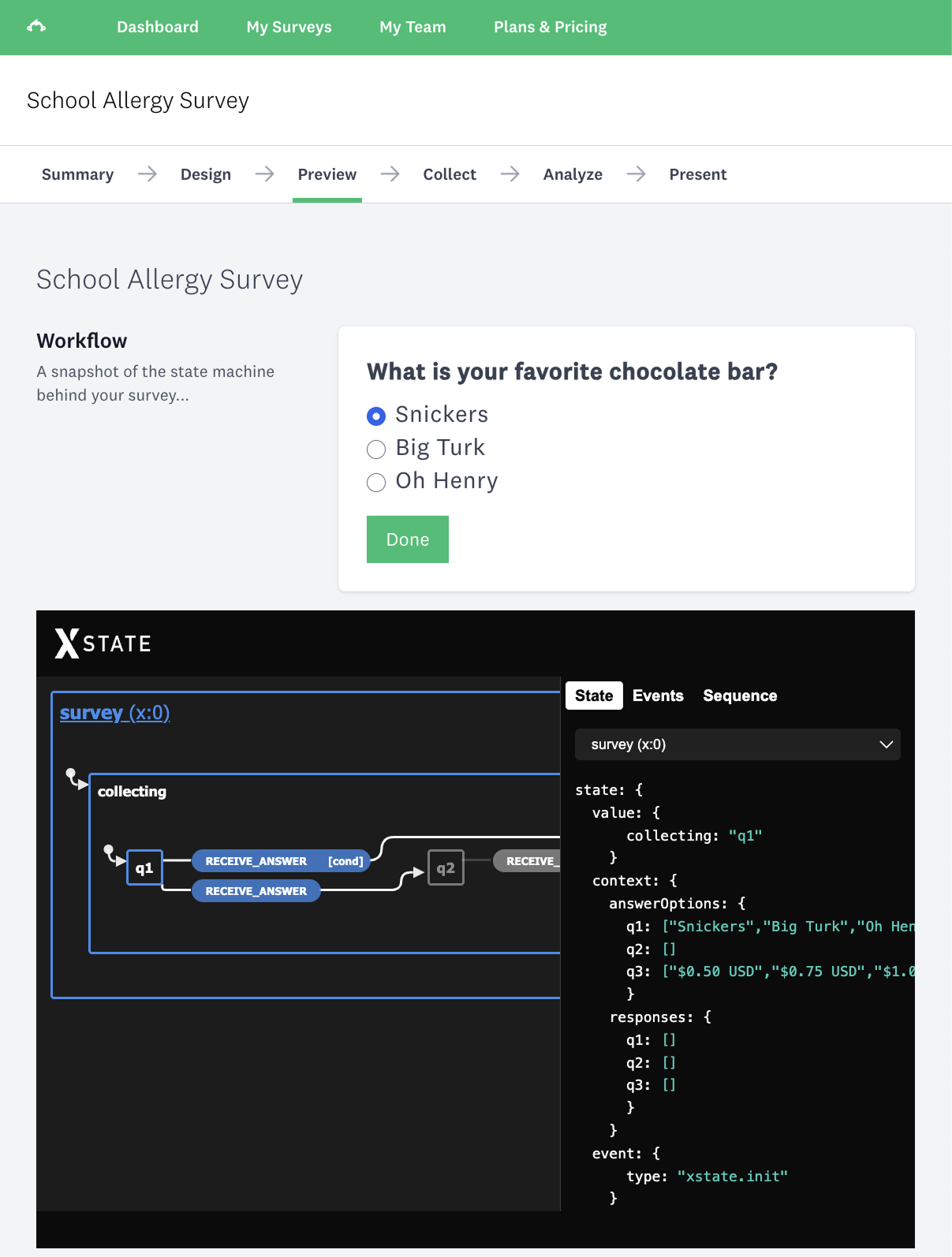

Events fired randomly, state changed, and debugging was an exercise in frustration, requiring a detailed specification of “the framework” open and a lot of trial and error to trace code execution when debugging. I ended up building a proof-of-concept using XState v4.26.1 during one of our hackathons, and I recall thinking:

this entire workflow, end to end, feels like it should be a state machine, what would it look like if we had survey creators use a GUI to produce a state machine definition that we could serialize in our db as the source of truth, and then when survey takers go to take the survey, we reinflate that definition and have them run it live in their browser

I was pretty convinced this could work, and the POC provided enough direction to give me confidence.

The scenario I tested with was a school allergy survey. Three questions, starting with one about chocolate bars. The idea was that a survey author could configure conditional branching logic in the GUI — if a respondent picked a chocolate bar that didn’t contain nuts then the follow-up question about nut allergies wouldn’t apply and should be skipped.

Simple enough to explain, but it maps perfectly to a state machine: each question is a state, each answer is an event, and branching logic is a guard.

Because I like code, here’s the core of the POC (syntax is XState v4, so it’s old and out of date compared to v5, but illustrative enough to get the gist):

// xstate v4 syntax from ~5 years ago

import { Machine } from 'xstate'

const surveyTakingMachine = Machine({

id: 'survey',

initial: 'q1',

context: {

answerOptions: {

q1: ['Snickers', 'Big Turk', 'Oh Henry'],

q3: ['$0.50 USD', '$0.75 USD', '$1.00 USD'],

},

},

states: {

q1: { // What is your favorite chocolate bar?

on: {

RECEIVE_ANSWER: [

{

target: 'q3',

cond: (context, event) => {

// no nuts → skip the nut allergy question

return event.answer === context.answerOptions['q1'][1]

},

},

{ target: 'q2' },

],

},

},

q2: { // What is your schools policy on peanut allergies?

on: { RECEIVE_ANSWER: [{ target: 'q3' }] },

},

q3: { // What is a fair price for a chocolate bar?

on: { RECEIVE_ANSWER: [{ target: 'completed' }] },

},

completed: { type: 'final' },

},

})

The builder (“config”) side dynamically generated these machine configs from user input. You’d add questions in a UI, define answer options, and input branching logic as a text expression like Q1 = C2 => SKIP TO P3 (if Question 1, Choice 2 is selected, skip to Page 3).

Obviously this was a POC — a production version would need a more robust expression language — but for the purposes of proving the concept it was sufficient. Every change regenerated the machine config in real-time — you could see the JSON update as you built. The config was then serialized to storage.

The survey taker doesn’t know there’s a state machine. They just see questions, one at a time, with branching that “just works”.

My design notes from the time are interesting to revisit in the age of AI:

SurveyTakingOneAtATimeMachine

SurveyTakingClassicMachine

SurveyTakingConversationMachine

A conversational survey (SurveyTakingConversationMachine) is, in hindsight, just a voice agent running a state machine. I just didn’t have the voice agent yet.

The POC didn’t seem to get much traction internally, which had me scratching my head — the approach seemed like such a natural fit to me. Maybe the idea was too ahead of its time, maybe XState wasn’t mature enough for the team, or maybe I just wasn’t good at pitching. 😅

A more likely reason is that my POC hadn’t fully solved the serialization/runtime challenges; I had conceptualized how it would work — a machine definition as a JSON blob serialized in your database and inflated at runtime — but I didn’t show how that could happen aside from a basic demo using localStorage.

XState v4 had not yet formalized use of the Actor model, which sits beautifully on top of a state machine; in v5, XState made this explicit — every running machine is an actor, and you get getPersistedSnapshot() to serialize the full actor state and restore it later with createActor(machine, { snapshot: restored }).

In 1999, van Gurp & Bosch were solving the same problem with XML and Java serialization:

FSMAction components are instantiated, configured and saved to a file using serialization. The saved files are referred to from the XML file as .ser files. When the framework is configured the .ser files are deserialized and plugged into the FSM framework.

The round-trip from database to runtime and back that they were building with XML and .ser files is the same round-trip XState v5 gives you with JSON and getPersistedSnapshot().

Deterministic Core, Agentic Shell

I keep coming back to this idea of core/shell as I repeatedly see the pattern of legacy applications that could be simplified by using a state machine in the core.

Which brings me back to where I started: Gary defined the functional core and imperative shell as a pattern that informed the type of code and approach to testing that I have seen work extremely well in practice. I think we are now entering a time where we can apply a similar architectural lens to apps that leverage LLMs.

Because I lack originality, and I really like Gary, I’m calling it deterministic core, agentic shell.

The trick as I see it is, all these companies want to build “agentic” features and rely heavily on the LLM, which frequently (and rightfully) violate every software engineer’s sensibilities around determinism. Evals, LLM-as-judge, vibes-based-testing, and all of the “rigor” around how to “test” prompts and use of agents is all well and good, but for my money nothing beats the fast feedback loop and confidence of a sufficiently isolated unit test with pure functions.

So, similar to how functional core was Gary’s answer to testability in a world full of side effects, my assertion is that state machines are the answer to determinism in the era of AI agents. I have seen time and again that if we draw a larger box around that core and try as hard as possible to shove all the things that are important into it, and into a state machine, that the layers above (both imperative and agentic) become minimized, reducing risk, and making it much easier to verify correctness in the core of the system.

A Pragmatic Reference Architecture

I’ve been spiking on a project with Jon Girard and Michael Timko and applying these ideas — the heritage from van Gurp & Bosch, the configuration-driven approach from Fantasm, the machine-as-source-of-truth thinking from my SurveyMonkey POC — and it is proving highly effective at validating deterministic core, agentic shell.

Here’s the broad strokes of what we’ve been working with:

+--------------------------------------------------+

| Telnyx (telephony) |

| caller <-> WebSocket <-> u-law 8kHz audio |

+--------------------------------------------------+

| Agentic Shell |

| |

| Mastra Agent + OpenAI Realtime (voice LLM) |

| - system prompt constrained by machine state |

| - available tools constrained by machine state |

| | |

| | tool calls |

| v |

| Mastra Tools (bridge) |

| - translate agent intent -> machine event |

| - return machine state -> agent |

+--------------------------------------------------+

| Deterministic Core |

| | |

| | events |

| v |

| XState Machine |

| - states, transitions, guards, actions |

| - pure functions, trivially testable |

+--------------------------------------------------+

| Postgres (storage) |

+--------------------------------------------------+

If you have worked with Mastra before, there are some great framework primitives that will let you build a workflow, agents, and even individual tool calls; it’s very easy to put all your eggs in the Mastra basket, and it is good at what it does, but one of my hard-learned engineering principles is it’s better to minimize coupling to 3rd party systems and tools and put as much of your business logic into code that you own.

When the “system” is a sprawl of connections to 3rd party services or libraries, the surface area of your codebase becomes harder to test, change, and that much more of a liability.

Jason Collins, the CTO at Vendasta I mentioned earlier, used to say “show me the code!” whenever someone pitched an idea in a meeting.

I’ve always loved that — so in that spirit, here’s some code!

A Deterministic Core

Let’s use a simple identity verification flow as our example — the kind of thing you’d encounter at the start of any phone-based workflow.

Everything important lives in the machine definition:

// xstate 5 syntax

import { assign, setup } from "xstate";

export const sessionMachine = setup({

types: {

context: {} as {

attempts: number;

verifiedId: string | null;

},

events: {} as { type: "VERIFY"; id: string },

},

guards: {

isValidId: ({ event }) => event.id === "6789",

},

actions: {

incrementAttempts: assign({

attempts: ({ context }) => context.attempts + 1,

}),

setVerifiedId: assign({

verifiedId: ({ event }) => event.id,

}),

},

}).createMachine({

id: "session",

initial: "greeting",

context: { attempts: 0, verifiedId: null },

states: {

greeting: {

on: {

VERIFY: [

{

guard: "isValidId",

target: "verified",

actions: ["incrementAttempts", "setVerifiedId"],

},

{

target: "awaitingVerification",

actions: ["incrementAttempts"],

},

],

},

},

awaitingVerification: {

on: {

VERIFY: [

{

guard: "isValidId",

target: "verified",

actions: ["incrementAttempts", "setVerifiedId"],

},

{ actions: ["incrementAttempts"] },

],

},

},

verified: { type: "final" },

},

});

The guard (isValidId) is a pure function. The actions are deterministic assignments. The transitions are explicit. You can unit test this without any LLM, any network, any voice connection. Deterministic core.

Bridge: Tools That Connect Agent to Machine

The LLM doesn’t decide if the user is verified. The machine does. A Mastra tool is the thin bridge between them:

export const verifyIdentityTool = createTool({

id: "verify-identity",

description:

"Verify the user's identity by checking their 4-digit verification ID.",

inputSchema: z.object({

id: z.string().describe("The 4-digit verification ID provided by the user"),

}),

execute: async ({ context, runtimeContext }) => {

const sessionActor = runtimeContext.get("sessionActor") as SessionActor;

// Agent -> event to the machine — machine decides what happens

sessionActor.send({ type: "VERIFY", id: context.id });

// Machine state is the source of truth

const snapshot = sessionActor.getSnapshot();

const verified = snapshot.value === "verified";

return {

verified,

message: verified

? "Identity verified successfully."

: `Incorrect verification ID. (Attempt ${snapshot.context.attempts})`,

attempts: snapshot.context.attempts,

};

},

});

The tool translates what the agent heard into a machine event, and reports the machine’s verdict back. The agent can be “creative” with language (still working on this part, so YMMV here); the machine is authoritative on state.

Orchestration: Machine State Drives the Agent

This is where things get fun; dynamic tool swapping. The agent’s capabilities — both its instructions and its available tools — expand and contract based on the deterministic core’s state:

// Before verification: agent can ONLY verify

export const preVerificationTools = [

mastraToolToOpenAI("verify-identity", verifyIdentityTool),

];

// After verification: agent gets financial tools

export const postVerificationTools = [

mastraToolToOpenAI("verify-identity", verifyIdentityTool),

mastraToolToOpenAI("getTransactions", getTransactionsTool),

mastraToolToOpenAI("getAccounts", getAccountsTool),

];

When the machine transitions to “verified”, the agent’s entire configuration gets swapped in Mastra — different instructions, different tools:

// Create session state machine and inject into agent's runtime

sessionActor = createSessionActor();

const runtimeContext = new RuntimeContext();

runtimeContext.set("sessionActor", sessionActor);

await agent.voice.connect({ runtimeContext });

// Start with limited tools and verification-focused instructions

agent.voice.updateConfig({

instructions: `You are a helpful financial assistant.

The user has NOT been verified yet.

Ask them to provide their 4-digit verification ID.

Do NOT discuss any financial details until verified.`,

tools: preVerificationTools,

});

// When the machine transitions to "verified", unlock everything

agent.voice.on("tool-call-result", (data) => {

const { toolName, result } = data;

if (toolName === "verify-identity" && result?.verified) {

agent.voice.updateConfig({

instructions: `You are a helpful financial assistant.

The user has been successfully verified.

Use get-transactions and get-accounts to help them

with their finances. Be conversational and helpful.`,

tools: postVerificationTools,

});

}

});

The machine transition (greeting → verified) is deterministic and testable. The consequence of that transition — swapping out the agent’s entire instruction set and available tools — is where the agentic shell gets reconfigured, and is also deterministic and testable.

Scaling: A Real Voice Workflow

The code above is simple on purpose, but early tests and spikes have me confident that the pattern works. Imagine a production voice agent where callers dial in and speak to an AI assistant to complete a multi-step workflow over the phone:

Telnyx handles telephony and streams audio over a WebSocket. Mastra connects to the OpenAI Realtime API for speech-to-speech — the caller speaks naturally and hears natural speech back. The round trip for a single turn looks like this:

1. Caller speaks

→ Telnyx streams audio (μ-law, 8kHz) via WebSocket

2. OpenAI Realtime processes speech

→ Mastra forwards audio to OpenAI

→ Speech-to-text + LLM reasoning

3. LLM calls a tool

→ take_action({ action: "SUBMIT_ID", params: { id: "123456" } })

→ Tool runs: machine.send({ type: "SUBMIT_ID", id: "123456" })

→ Machine transitions: greeting → verifying_identity

→ Tool returns: { success: true, nextStep: "ask_for_details" }

4. OpenAI generates response

→ Uses tool result to generate spoken response

→ "Thanks, I've got that. Now, could you tell me which

account you'd like to work with?"

5. Audio plays to caller

→ Mastra → Hono API → WebSocket → Telnyx → phone

The agentic shell (Mastra + OpenAI) handles everything about the conversation — hearing the caller, interpreting speech, generating natural responses, handling “ums” and false starts and off-topic questions. Early signs are good, and one happy finding: the OpenAI realtime voice model supports interruptions and bi-directional voice communication out of the box.

The deterministic core (XState) handles everything about the workflow — what state we’re in, what’s valid, what happens next. The tools are the membrane between them.

Two tools do the heavy lifting: get_current_state lets the agent ask the machine “where are we and what can I do?”, and take_action lets the agent tell the machine “let’s move forward.” The machine enforces the rules — its guards reject anything that doesn’t satisfy the business logic. The agent is creative about how to have the conversation; the machine is authoritative about what happens next.

export const get_current_state = {

name: "get_current_state",

description: "Get current state of the workflow for this session",

handler: async ({ sessionId }) => {

const machine = getMachine(sessionId);

return {

state: machine.state.value,

context: machine.state.context,

availableActions: machine.state.nextEvents,

};

},

};

export const take_action = {

name: "take_action",

description: "Advance workflow by sending an event to machine",

parameters: {

action: {

type: "string",

enum: ["SUBMIT_ID", "SELECT_ACCOUNT", "CONFIRM",

"ACCEPT_TERMS", "COMPLETE"],

},

},

handler: async ({ sessionId, action, params }) => {

const machine = getMachine(sessionId);

machine.send({ type: action, ...params });

return {

success: true,

newState: machine.state.value,

message: getStateMessage(machine.state.value),

};

},

};

The system prompt constrains the agent’s conversational behavior, while the machine constrains the workflow:

export const SYSTEM_PROMPT = `

You are a professional assistant helping callers complete a workflow over the phone.

RULES:

1. Be clear and patient. Use simple language.

2. Always disclose important information upfront.

3. Never rush the caller. Frame every step as optional.

4. If you don't understand, ask for clarification.

5. If something goes wrong, apologize and offer a retry or human transfer.

CONVERSATION FLOW:

1. Verify the caller's identity

2. Present available options, caller selects

3. Run validation, explain if ineligible

4. Disclose any fees or terms, confirm acceptance

5. Execute the action, confirm completion

TOOLS:

- get_current_state: Check where we are in the workflow

- take_action: Advance the workflow

`;

The system prompt also tells the agent how to talk; the machine tells it when. Language lives in the shell, logic lives in the core.

Boundaries

Applying the core/shell lens has helped me think about where to draw the boundary between agent and state machine, and we are now in a world where it is trivial to produce working concepts that can validate where that line should be.

One way you might think about this is something like “let’s start with one Mastra tool, getMachine, and the only thing it was able to do was get the next state from the machine.”

This is a decent place to start, but kind of fell over in short order because there’s some amount of non-determinism you need in order for an agentic voice solution to work well — the agent needs to interpret messy human speech, handle interruptions, deal with off-topic questions, and generally be flexible about how it gets the information the machine needs.

What I’ve found works better is more guard-rails in the system prompt for the tools and workflow, but the principle of having the agent calling the machine to figure out what’s possible and constrain the states and tools that can be called next has proven extremely valuable.

The primary motivation should immediately be clear: get to determinism as fast as possible.

The voice agent interprets the caller’s input (non-deterministic), figures out what they’re trying to do (non-deterministic), and then immediately hands off to the machine (deterministic). The machine decides what’s valid, what the next step is, and what tools become available. The agent gets back a structured result and turns it into natural speech (non-deterministic again).

The non-deterministic parts are thin — the deterministic core is thick and does the actual work.

Lineage

I fell into an obsession with state machines as an architectural pattern by accident. I got to learn from Shawn, Jason, and Kevin at Vendasta, who were drawing on the pioneers that came before them. And I suspect there are more through-lines worth tracing, by revisiting old whitepapers and watching how ideas get refined as they move from theory to practice.

| Era | Tool | Pattern |

|---|---|---|

| 1955-56 | Mealy & Moore | original FSM models, “machines” |

| 1999 | van Gurp & Bosch | config vs runtime split, solid architecture |

| 2008-2011 | Vendasta / Fantasm | YAML-configured FSMs on appengine taskqueues |

| 2012 | Gary Bernhardt | functional core, imperative shell |

| 2020 | SurveyMonkey POC | xstate machine defs generated from a GUI, serialized, run in browser |

| 2025-26 | XState + Mastra | deterministic core, agentic shell |

Every time I pick up a new codebase, I find the same thing hiding under the surface — a half-baked state machine that nobody drew on a whiteboard first. Events firing into the void, state scattered across a dozen files, transitions implicit in if/else chains or switch statements three levels deep.

If you believe the chatter online, then you might feel like we are dealing with a lot more non-determinism these days; the imperative I/O Gary uses to frame his version of the shell definitely feels a lot more deterministic to me than an LLM that can hallucinate, go off-script, or confidently tell a caller something that isn’t true.

That makes the case for a deterministic core a lot stronger.